As a freelance sound designer, I’ve worked on a pretty wide variety of podcasts, including both fiction and nonfiction productions. While the format of these shows are night and day, my editing styles for each aren’t as dramatically different as you might think. I got my start in the podcast industry producing and sound designing fiction podcasts, and when I made the jump to freelancing — which came with a wider variety of show formats — I was surprised at how much my time with fiction prepared me to edit on the other side of the fence.

Here are the big four lessons I’ve taken from sound designing fiction podcasts to level up the nonfiction podcasts I work on. Whichever side of the fence you’re on, there’s probably a lesson here for you, too.

1. Editing a speaker is all about rhythm.

Every person, whether they’re real or a character on a page, has a natural rhythm that combines with other things — accent, dialect, word choice, etc. — to make up the unique way they speak. When you remove filler words or splice sections of an interview together to restructure its content, you’re breaking up that natural rhythm. This can result in edited sections feeling jarring or stilted, since the rhythm has been disrupted and not repaired in the edit.

When taking out a filler word or cutting out a large chunk of dialogue, pay attention to the speaker’s natural rhythm — you’ll notice it after listening to them speak for a while. Use that experience to follow their lead and match their rhythm in the edit, including where you choose to cut and how much space you leave between words. Don’t underestimate pasting in breaths and leaving in a filler word or two — your goal is to make the speaker sound extra polished, not like Siri.

2. The right music can fill in for visuals.

Unlike subjects in a video, all that speakers on a podcast have to convey their emotions and mood are word choice and tone of voice, so filling in those extra emotional details with the right background music is crucial. In that vein, don’t just think of music as what you put in to fill silence or mask some background noise. Think of this part of the process like scoring a movie scene. Use the creative associations we have with certain instruments, styles, and tempos to give us more information within the same auditory constraints.

For example, imagine you’re interviewing someone who teaches classes in the traditional Appalachian style of guitar fingerpicking. You might be tempted to play a bluegrass or blues track underneath, but dig a little deeper. Ask yourself: Who are these classes for? Are they popular or underfunded? The way your subjects feel needs to translate into the music you use to make the audience feel the same thing.

3. The audience will remember what stands out — and so will you!

This tip is a combination of writing and sound design experience, but it’s one I use for every single show I create: when cutting together an interview or sequence, do your first draft. Then, close the session and make a list of what happens in that content from just your memory.

When you compare this list to what you originally cut together, you’ll see what really stuck in your brain, and subsequently what is most important to strongly convey to your audience. After that, you can trim down the parts and points that you didn’t remember (and especially ask yourself why they weren’t as memorable to you). You’ll end up with a tighter piece as a result.

4. Pay attention to your character’s “place.”

In a fiction podcast, every character’s audio needs to be delivered completely dead and clean (that means no natural reverb, no background hum, and as little room tone as possible) so that, in the editing process, the sound designer can place it in a designed environment as seamlessly as possible. Even if you’re just putting a character in a conference room, clean audio will make it easier to put that character in that location with its specific reverb and tone — otherwise, the recording will clash with the designed space.

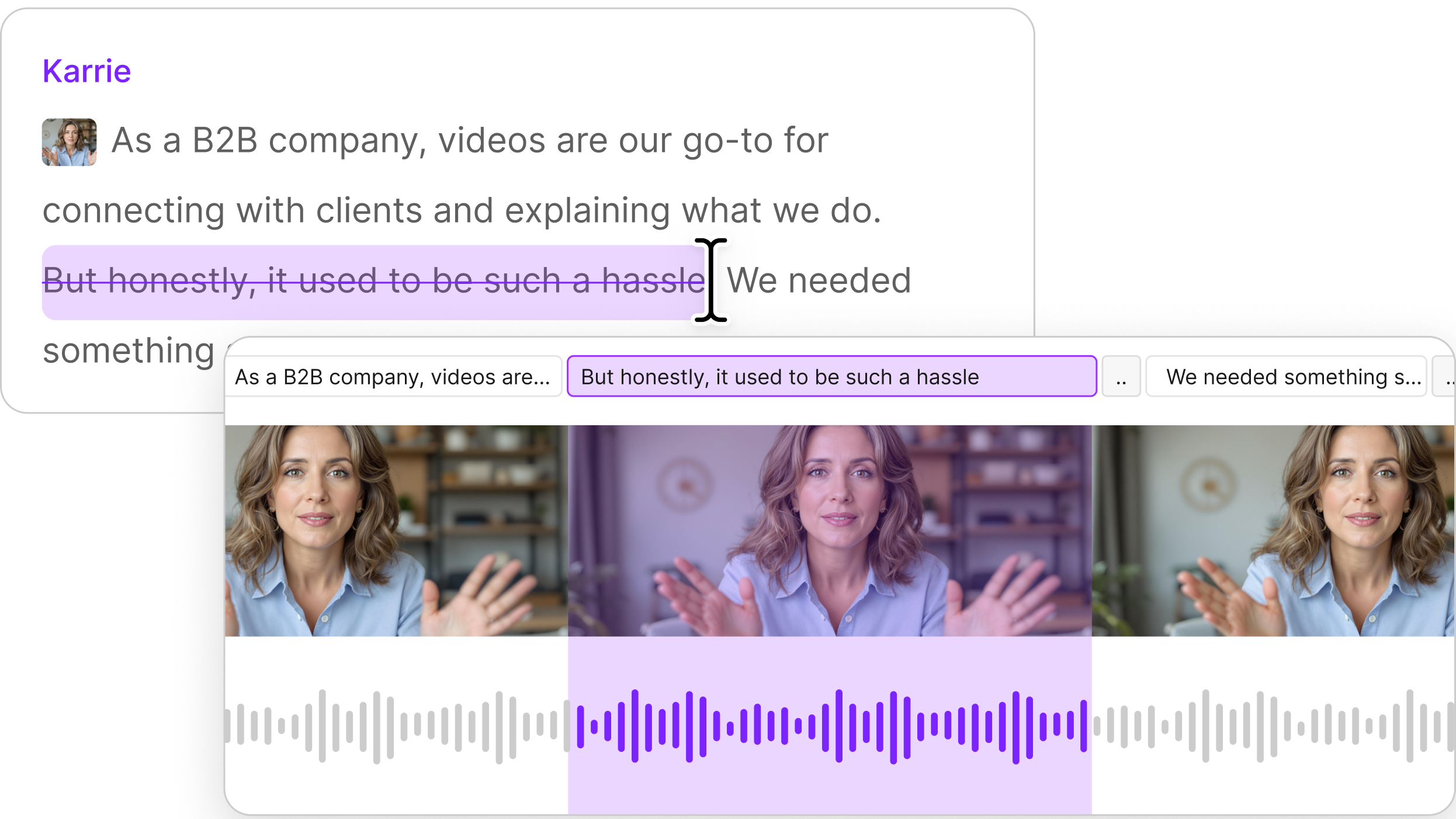

This is especially important when you have two or more characters in a location together. Every person needs to sound like they’re in the same space, regardless of microphone quality or recording environment. (Editor: Here’s the part where I hawk Descript’s Studio Sound feature, which does a great job of making everyone sound clean and clear with just a few clicks.)

Having this goal can be helpful when working with interview audio, too. Recording in a properly treated space and mastering your speakers’ audio not only for clarity, but cleanliness as well, can actually help your audience engage more with the material being presented.

What is clarity vs. cleanliness? Clarity is how understandable your audio is; the most basic requirement is being able to easily perceive what is being said without having to mentally sift through tons of distortion or background noise. Cleanliness is pickier: does your audio have as little reverb, background noise, and audible editing (compression, noise removal, etc) as possible to achieve the effect of listening to something recorded in a perfectly treated booth?

You can disregard this in some specific circumstances, such as a field recording where the environment is relevant to the story, but remember that your audience will be taking in every piece of information the recording presents. If it’s not relevant, ask yourself if this audio information is hurting or helping the listener’s immersion in the story.

Take a listen to these two Fresh Air interviews: one with Robert Gottlieb, and one with Michael Cecchi-Azzolina.

In both, the host has very clean, crisp audio that is so closely mic’d you can hear every swallow. Robert Gottlieb (and his daughter Lizzie) have present room tone and a bit of reverb, and the speakers themselves sound slightly muffled. Michael Cecchi-Azzolina, meanwhile, has audio that’s clean and crisp like the host. Which gives you the sense that both the interviewer and interviewee are in the same space together? It’s probably the one that matches the audio quality of the Fresh Air host — it certainly is for me as a regular listener.

Every time the speaker switches back and forth in the Gottlieb interview, I can feel myself taken out of the conversation a little bit from that noticeable change in location. Even when you don’t need to convince your listener that these two people are sharing a location for story reasons, our brains are wired to pick up and focus on these discrepancies. Your listener will have a more immersive and engaged experience if that locational shift is as imperceptible as possible.

%20(1).JPG)