This article originally appeared in Episodes, our newsletter. If you'd like insights on workflow and craft (like these) in your inbox every two weeks, you can subscribe.

Nobody spins a better yarn than Jad Abumrad. At Radiolab, More Perfect, and Dolly Parton’s America, he’s told as many memorable audio stories as any living creator.

On all of those projects, Jad weaves complex, nuanced, often surprising narratives. That’s what makes them so interesting. What makes them so affecting is the way each one cuts through the complexity to zero in on a fundamental, profound truth.

It’s not easy though. Jad acknowledged as much in a conversation with the winners of our Studio Sound contest (held in October, to see who could show the most impressive, creative uses of Studio Sound). Mark Oppenheimer, creator and producer of the Constitutional Landmarks podcast, asked for Jad’s advice on how to construct a tight narrative when you've got hours of recorded interviews.

His five-minute answer was basically a master class in workflow for storytellers. Even if you’re not telling the kind of big, unwieldy, profound stories Jad tells, or doing 5+ interviews per story, you'll want to read this

A storyteller's workflow

Step 1: Listen. To prepare himself to listen to the tape (all the interviews he's recorded) Jad finds a comfortable chair and tries to get himself into something akin to “a meditative mindset” where he’s open to and aware of anything that makes him react. That could be something that strikes him as odd, or surprising, or that makes him sit up and lean in, wondering what’s coming next. Or just a nice turn of phrase or an eloquent description of something important. What we take from this: don’t try to listen for anything. Just listen. See what grabs you.

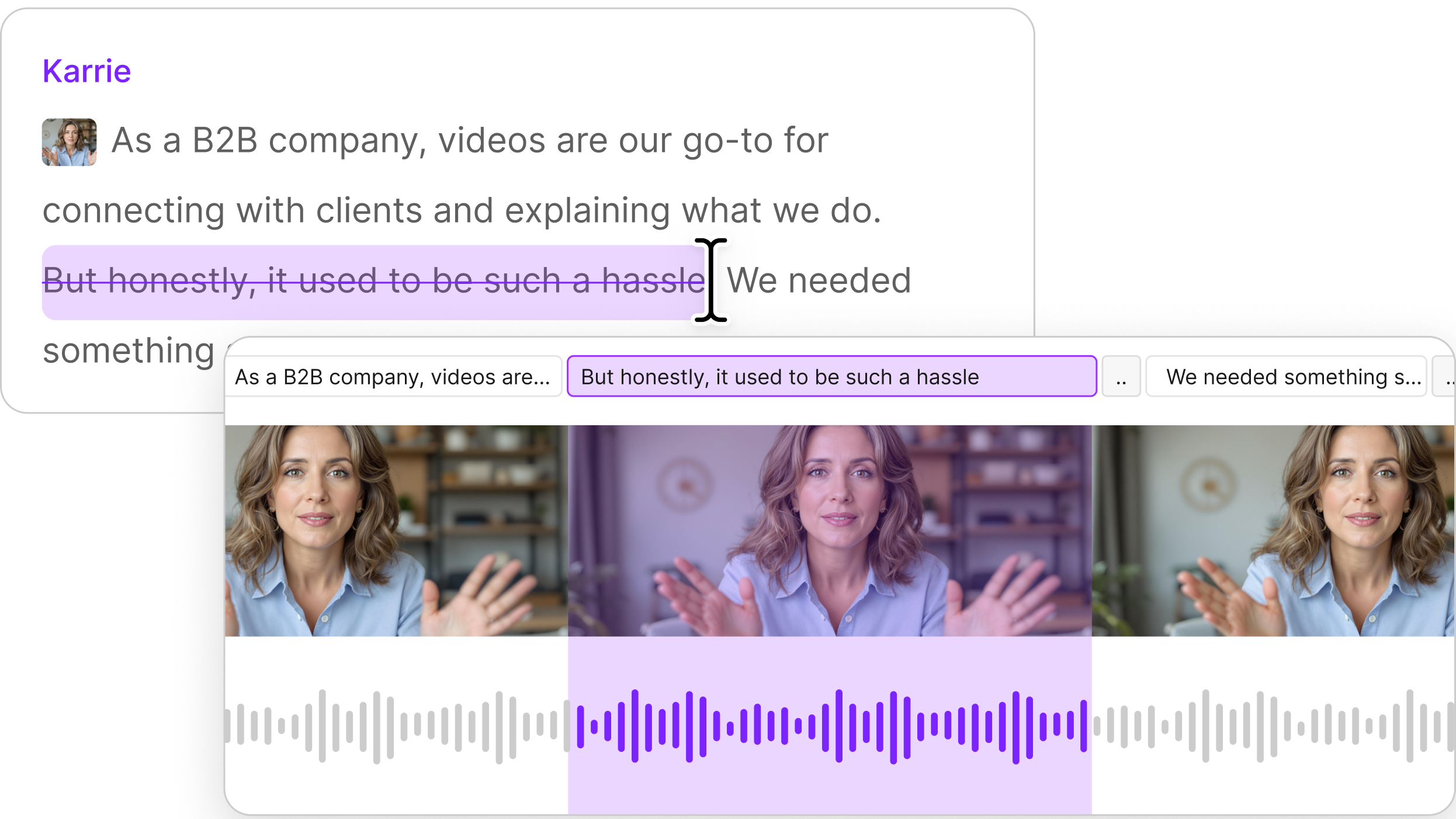

Step 2: Clip to composition. Alright, we made it this far without talking about Descript. But now we have to because it’s what Jad uses to collect the moments that jump out at him during his almost-meditative listening. In the transcript view, he highlights (probably by pressing ⌘⇧H) the part that just caught his attention or caused a reaction; then he clips it to a new composition (using ⌘C, I’ll bet) where he’s collecting all those moments. When he’s done listening to all the raw recordings, he’ll listen to the new composition, which is now a distillation of all the most resonant moments he’s captured. [Note: you too can copy highlights and clip to composition]

Step 3: Tell a friend. Jad listens to the best-of composition a few times himself, to get a sense of the story. Then he walks away from it, finds someone who knows nothing about it, and tells them the story himself, in his own words. As they listen, he's taking note of the moments where their eyes get wide, they lean in, or otherwise engage—and the moments where they lose the thread. Jad calls this a “physical kinetic act of telling the story to see what works.” So you want to be in the room with the person, or at least on Zoom or somewhere you can see them.

Step 4. Summary + First cut. Based on what he observed from whoever he told the story to, Jad writes up a quick summary; it's like a treatment, or an abstract—just two or three paragraphs that lay out what happened, describe the important inflection points, where he’ll bring in quotes, and from whom. Then he pulls together all the corresponding clips to make a very rough audio version of the summary. This is generally still 4-5 times longer than the final cut will be.

Step 5. Ask the tape. Here’s where it gets mystical. Once Jad has his assembled his rough version, he asks himself, “does the tape like this?” If the tape doesn’t like the way he’s laid it out, he’ll get in and start shifting things around—editing the recordings or adjusting the narrative until the tape is in the right order, until the tape says, in Jad's words “I like this!”

Now obviously the tape isn’t going to actually talk to you—it only talks to Jad. But hopefully you get the idea: the material you’ve recorded may not always fall neatly into the story you have in your head, or on paper. Maybe an interviewee never explicitly says the big thing you took away from their interview, so you have to find a different way to get that point across. That's why you ask the tape.

Step 6. Edit. Only now, after all of this, does Jad dive into editing. This is crucial. Before you start splicing clips together, adding fades, removing filler words, and so on, you want to have your story locked down.

This is also the part that applies to every creator, whether you’re doing narrative journalism, a topical monologue, a seat-of-the-pants interview show, whatever. Don’t start the technical editing until you’ve got the content squared away. Jad learned this the hard way. “I used to just jump in the tape and start editing,” he told our contest winners. “And I would try to edit my way out, and I would get so lost.”

You may not have enough material to get lost in. But you almost certainly have enough to drive yourself to madness if you keep running into narrative dead-ends. And you probably don’t have much time to spare. Most creators are pushing themselves to exhaustion just trying to finish what they started, and to make something they can feel good about.

So take whatever you can from Jad’s advice. We hope it helps you work faster, or smarter, or both.

.png)