This post was written by James Shield, senior producer for Stories of Our Times, a daily news podcast from The Times and The Sunday Times of London. It was originally published on his blog and is republished here with permission.

Using archive

There are a few podcasts like ours, and one of the things that distinguishes the really good ones from the rest is excellent use of archive. (Feel free to skip this bit if you’re just interested in the tech.)

The archive in my stories is usually doing one of several jobs. Often it’s to give a sense of “everyone’s talking about this,” the buzz of news coverage, or to take us back to a point in time. (See footnote 1 below.)

There are also moments when you just need to hear the delivery of a particular line. Take for example health secretary Matt Hancock’s haunting delivery of “Happy Christmas”.

Most of the above is not hard to find. You can get by on searching YouTube, noting down the time and date when you hear something grabby on the news, or using Twitter bookmarks to keep track of viral videos. Sometimes YouTube videos have transcripts you can search, which is handy.

But some of the most interesting ways to use archive are to spot patterns listeners may have missed, context they may have forgotten about, and depth beyond the handful of clips they’ve already seen on TV news and on Twitter. And that’s the most difficult material to get, especially in a hurry. Ordinarily hunting for it wouldn’t be an efficient use of time on a daily program: you could spend half an hour finding just the right 15 seconds.

Since July, a completely different way to source archive has become possible.

Making audio searchable

What if instead of hunting for the right clip, you could throw everything into an audio editor – just an absurd quantity of material – and then keyword search it?

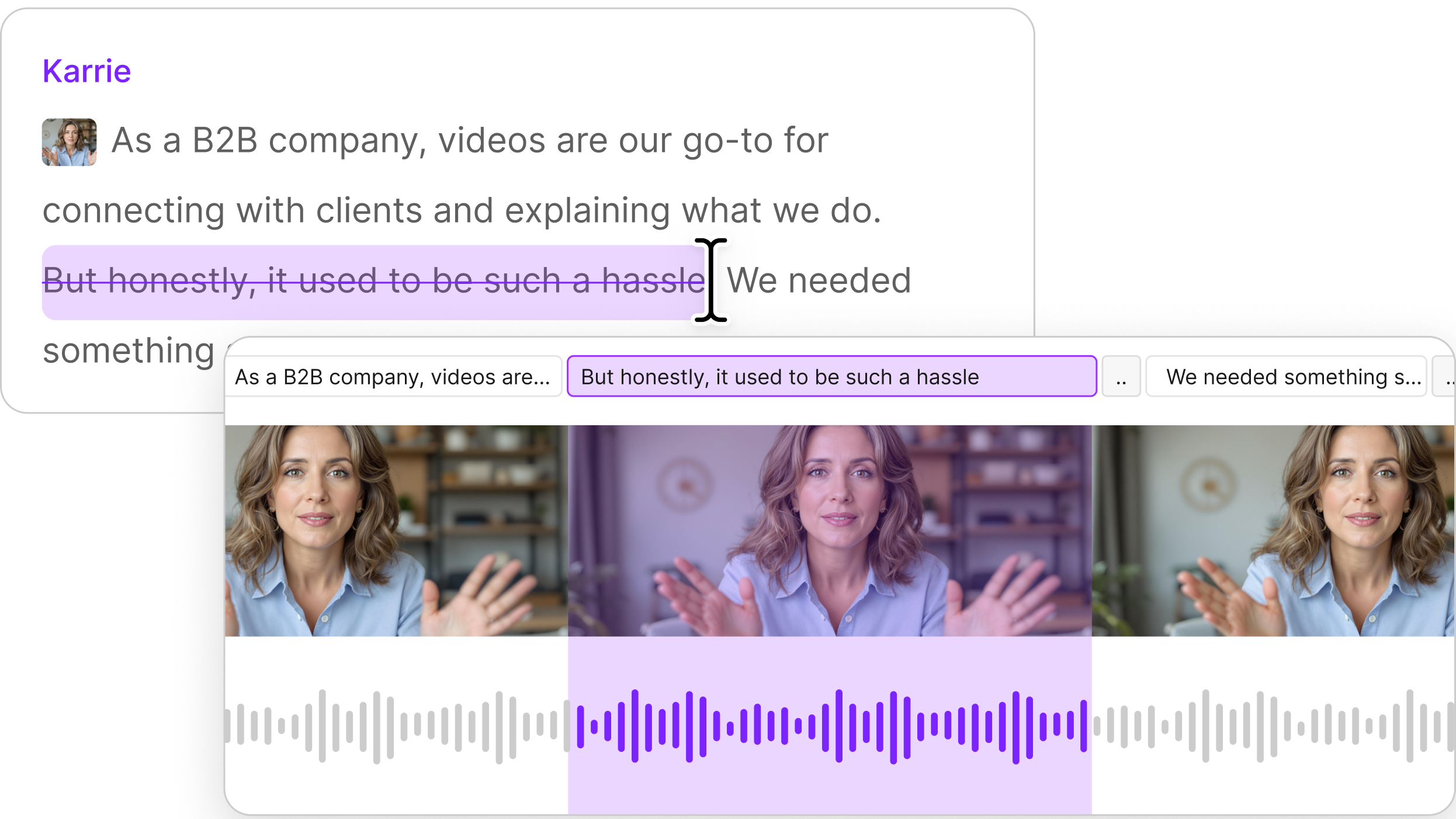

We’ve been doing the bulk of our editing in Descript since we were piloting in January 2020. It transcribes all your material and you can edit the audio directly from the transcript and in collaboration with others. It’s like Google Docs for sound. (See footnote 2 below.)

A year ago Descript was just on the margin of being stable enough for us to work in. It has become more reliable since then, and a handful of new features have made it more powerful. One of those is the addition of “copy surrounding sentence” to its search function.

In seconds, you can search all the transcribed audio in a project by keyword, copy not just the audio of the keyword being said but the sentence it’s part of, and paste all of those sentences into a new composition.

For example: what if you could search every UK government coronavirus briefing, data briefing and TV statement by the prime minister since the start of the pandemic and instantly stitch together every time someone was accidentally on mute? Well, here it is, made from a project containing 94 hours of audio from 128 briefings and statements.

Or how about every time the prime minister said ‘alas’?

Or what if you simply enjoyed that time ITV’s Robert Peston started his question to the chancellor with “oh shit” and wanted to hear it again? Here you go.

More seriously, what if you could search for the first time government scientists mentioned the possibility that a new vaccine-resistant strain of the virus could emerge, and every time it’s come up again since? Have a listen to the opening few minutes of this episode.

The firehose

We first used this technique on the night of the US presidential election, when we recorded, produced and mixed the next day’s episode between 11pm-5am.

This time we wanted speed as well as searchability. What I ended up building gave us the ability to keyword-search coverage from CNN, CBS, NBC and Times Radio as the night unfolded.

Using what I’m calling the ‘searchable news firehose,’ we were able to search for ‘too close to call,’ ‘long night,’ ‘Hispanic voters,’ ‘Florida,’ and so on, and instantly paste together the audio of all the sentences containing those phrases from a whole night of coverage.

Here’s a quick example, made part-way through the night.

How it was built

Three browsers playing the live streams from each of the networks – plus a radio streaming app – were recorded into Audio Hijack. (To get the TV network streams I used my colleague Matt ‘TK’ Taylor’s excellent VidGrid, which every news producer should know about.)

Audio Hijack started a new chunk of those recordings every 15 minutes, saving them into a Dropbox folder.

I used Zapier to monitor that Dropbox folder and – using Descript’s Zapier integration – automatically import the audio into a Descript project to be transcribed and made searchable.

Which I admit sounds like overkill for a podcast.

But now it’s built, we can spin it up whenever a breaking news event is unfolding, as we did on January 6 during the insurrection at the US Capitol.

New possibilities

There’s much more to being an audio producer than being a technician, but having a good grasp of new technologies can change the sort of creative projects that are conceivable.

What could you make if the audio of every PMQs was instantly searchable in your editing app? Every presidential speech? Every NASA live stream?

With tools like this now at our disposal, we’re about to hear some really creative new uses of archive. This will be especially good for low budget and quick-turnaround productions without the resources of a documentary feature film.

Oh, and this works for video too. Take a look at what it’s doing to US political ads.

Listen and subscribe

I wouldn’t be doing my job as a podcast producer if I didn’t ask you to subscribe to Stories of Our Times. Here’s a recent episode I produced, talking to doctors across the country:

James Shield · Could the NHS be overwhelmed in two weeks?

1. And it should be woven into the storytelling. There’s an approach to editing news podcasts that goes something like: interviewee mentions speech by a politician, 20-30 second clip from speech plays, interviewee gives analysis of speech. I think that’s dull. I prefer the main voice and the archive to tell the story together, with shorter clips and more staccato editing, finishing each other’s sentences, using the clip to deliver the lines only the politician can say: just the color.

2. One advantage of starting something new and having a piloting period is being able to experiment with workflows, in a way that would be much more difficult post-launch. As far as I can tell, the Stories of Our Times team were among Descript’s earliest adopters in the UK, and may still be their biggest UK customer, although I don’t know that for sure.