This article originally appeared in Episodes, our newsletter. If you'd like insights on workflow and craft (like these) in your inbox every two weeks, you can subscribe here.

Finding the right tone of voice for your podcast (or video) ought to be simple: speak naturally, sound like yourself, and ignore anyone who gives you grief about it (they probably will, especially if you’re a female creator).

But for whatever reason it’s not simple at all for a lot of us: put us in front of a mic and our speech starts sounding stilted, or just unnatural. Talking too fast or slow, distracting verbal tics, weird mouth noise, reading in a way that sounds like reading – all common challenges for new creators, and even for some veterans. It’s a problem because all of those things create barriers between your audience and your ideas, your stories, your content.

Like every part of the craft, the best way to master your tone of voice is by just grinding away at it. Try, fail, learn, get better. But also like anything, creators who’ve already slogged through the trial-and-error know a few tricks. We talked to a handful to get some advice on finding a voice that works for you and your audience. Here are the best things we heard.

Steal someone else's voice

Especially when you’re just starting out, there’s nothing wrong with just picking someone whose show you admire and trying to sound like them. Ideally it’s someone in your genre, or your niche; you’ll know their tone works for your subject matter, and it’ll be familiar to your audience. It's also useful to pick someone you identify with — someone who sounds like the community you're trying to represent.

Kat Carlton cut their teeth as a newscaster at an NPR affiliate in Indiana, and now produces podcasts, including Things You’re Too Embarrassed to Ask A Doctor, at University of Chicago Medicine. Over the years they’ve learned to tune their voice precisely, to the type of show they’re doing and the audience they’re talking to. But when they started out, Kat just tried to talk like the podcast hosts they’d grown up with — Ira Glass and Jad Abumrad.

Not that they did a straight imitation; Kat just tried to copy those creators’ pacing, rhythm, and tone. Then, both when they were recording and editing, they listened for the parts that didn’t feel like themself. Over time that led Kat to the voice they wanted: professional, conversational, and distinctively them.

Nowadays, when Kat’s starting a new podcast, they put themself in the audience’s shoes. “What kind of person would I want to hear from about this topic,” they ask themself. “Someone warm and serious? Someone funny and silly?” The answer sets the tone.

Slow down

A lot of verbal tics can be avoided just by slowing your delivery. You don’t want to go too slow, but most of us talk faster when we’re nervous or self conscious, so forcing yourself to talk slower will often make you sound more natural.

Talking slower, and leaving space between sentences and phrases, even words, also paves the way to use editing to make yourself more eloquent. My colleague Kevin O’Connell, a product specialist at Descript and a veteran podcast producer who’s edited and coached many hosts over the years, points out that editing out extra space is a lot easier than trimming extra words. Deep breaths are easy to remove too, as long as they’re between sentences (and if you can’t help breathing while you talk, there’s always Studio Sound).

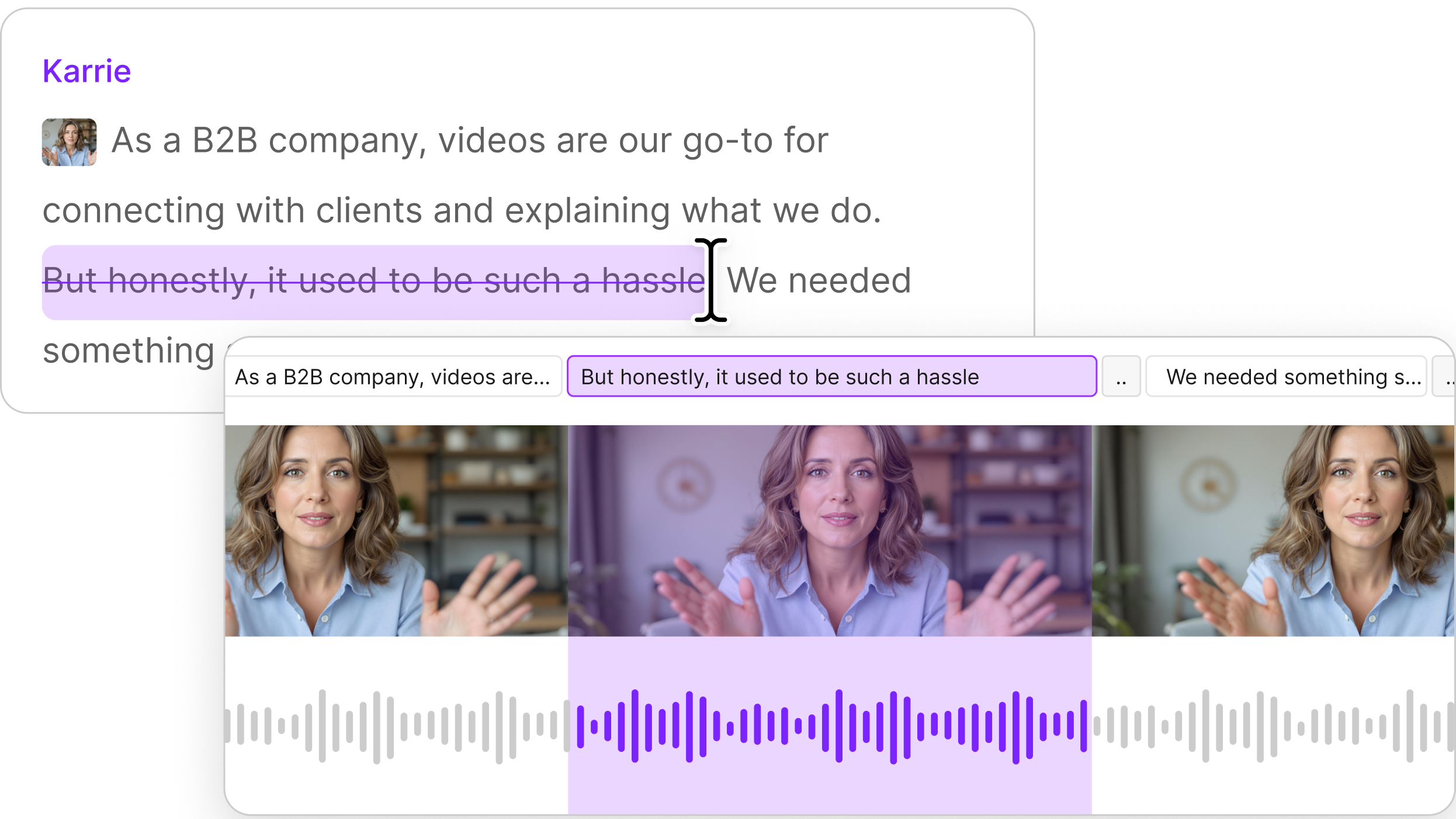

So try building in pauses — and then when you hear yourself doing the stuff you want to avoid — excessive filler words, awkward enunciation, stumbling over a phrase, and so on — you can stop, take a breath, and try again. If you’re editing in Descript, it’ll be fast and easy to edit out the bad takes in the transcript.

Break it down

Hearing the sound of our own voices scares the bejesus out of most of us. A lot of creators really struggle with hearing themselves. You have to push past that, which is largely a matter of just getting used to it. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be self-critical, or you can’t get better. Your tone of voice is part of your craft.

Kevin’s advice: start by listening carefully to your voice, then try to describe it as vividly as possible. If you don’t like how you sound, try to pinpoint exactly what’s bothering you. Then listen to some hosts you like, and see if you can determine how they’re different, or similar. You may find you’re not doing anything wrong, you just sound different.

Or you may find you’re doing something distracting — breathing too heavily, changing volume, making some annoying noise with your mouth, or whatever. Obviously you should edit that stuff out. But you also want to make a note of it, so you can work on trying to avoid it the next time.

Just going through that exercise can also help you get over hating your own voice. Rod Faulkner, host and producer of the Eye on Sci-Fi podcast, says treating his voice the same as any part of his craft, like deciding which parts of an interview to cut or adjusting his volume levels, is how he learned to stop cringing at the sound of himself. “Listening to yourself over and over, you start to hear your vocal performance dispassionately,” he says.

Ignore the jerks

It’s amazing how many experienced, accomplished creators have stories about overcoming deep insecurity about their own voice. Val Agnew, cohost of the DCOMmentaries podcast and founder of the Trident Network, grew up hating her “highly enunciated, lower-timbre tone” of voice. Then one day she heard her tone coming out of the mouth of Glen Weldon, on NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour. He called it “nerd voice.” Val grabbed onto that and hasn’t let go. “I am a nerd,” she says, with a tinge of defiance.

Kat Carlton likens the process of getting used to their own voice to “experiencing a little ego death.” Rod Faulkner has written ardently about learning to love his voice.

Hopefully working on the stuff we’ve described here will help you fix the parts of your voice that actually need fixing, and get more comfortable listening to yourself.

Once you’ve done that, ignore anybody who tells you they don’t like it. Our best advice on dealing with the haters is to emulate Mandy Matney, the decorated journalist who reports, writes, produces, and hosts Murdaugh Murders, a deep-dive investigative podcast.

No sooner had the first episode published than Mandy started getting nasty comments about her voice. In the opening moments of the second episode, she put the matter to rest: “I can’t change my voice,” she said. “This is it. Take it or leave it.”