Do your job, do it well, do no harm.

This is the opening line to Jo Healey’s Trauma Reporting: a journalist’s guide to covering sensitive stories. When I first started freelancing, I read Healey’s book obsessively cover to cover. My copy is full of highlights and scribbles. I remember feeling anxious I might forget something when conducting an interview that demanded my utmost sensitivity.

The fact is, filmmakers and journalists alike want to hear from ordinary folks with extraordinary stories. Extraordinary stories aren’t always positive experiences — sometimes they come with loss, pain, and trauma. That can be hard for a person to talk about in an interview.

But all too often, interviews are extractive and can be triggering for interviewees. Mismatched expectations and a lack of communication can leave the person feeling deflated, or worse, deceived.

By learning some of the principles and techniques for preparing, conducting, and following up on a trauma-informed interview, you can approach the interaction with the confidence you’ll need to do justice to your source’s story while making the experience a more positive one for everyone involved.

Pre-interview preparation

Before you start the interview process, be prepared.

First, make sure you have a thorough understanding of the trauma your interviewees have experienced. The more prepared you are, the easier the interview will be.

Trauma can result from a wide range of experiences, such as accidents, abuse, environmental disasters, or war. It can happen during a single event or an ongoing situation, and can affect people in different ways, both mentally and physically. A traumatic event may have a person feeling anxious, embarrassed, irritable, or withdrawn. They might also experience physical symptoms like trembling, muscle aches, fatigue, or nausea. It’s important to educate yourself on the specific trauma your interviewee has faced so you can show up to your interview prepared, and with a good understanding of the context.

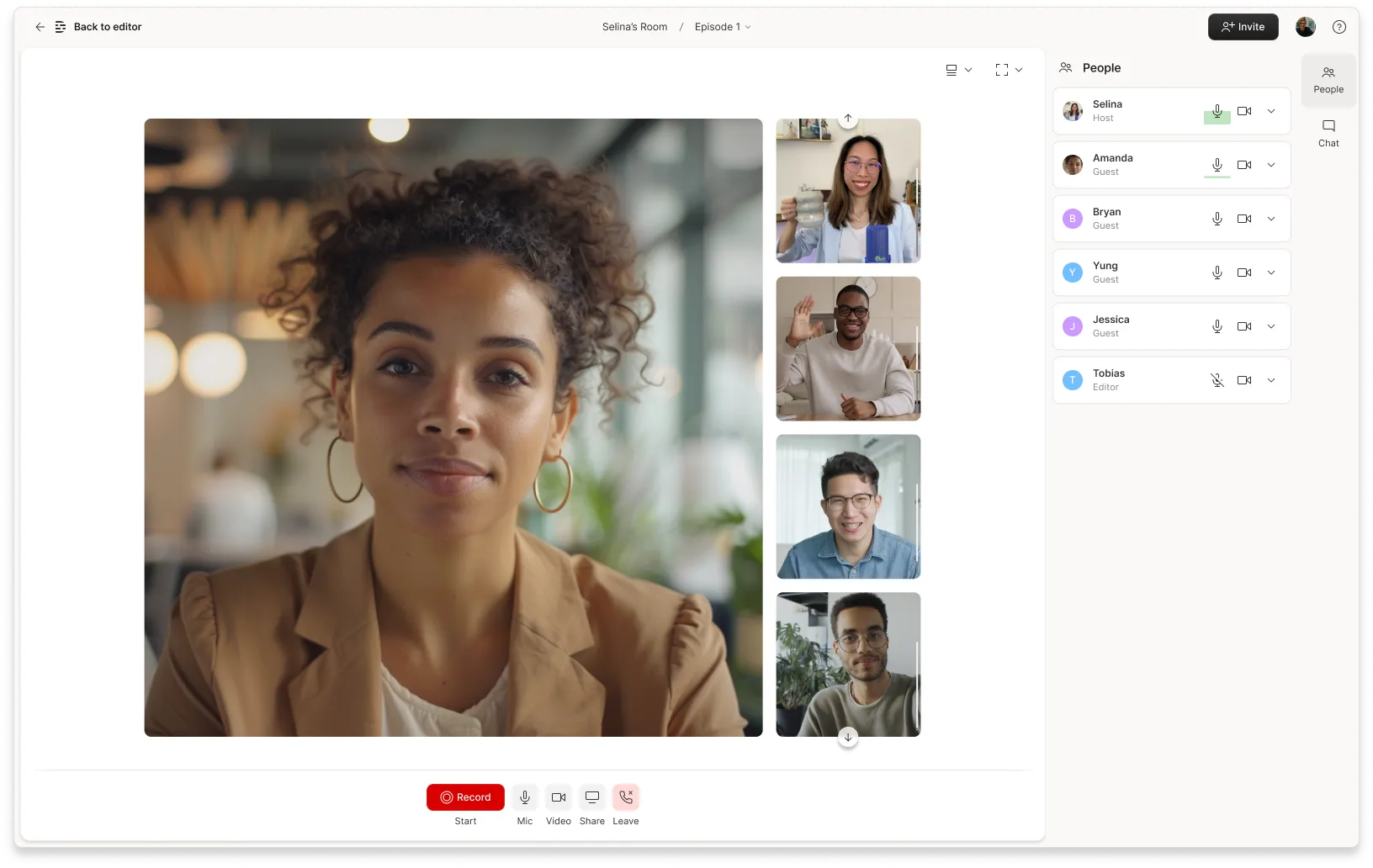

Consent is always important, but it’s especially important in trauma-informed interviews. The person you’re interviewing must be able to understand why you are interested in their story, what story you intend to tell, where it will be shared, and how many people will see it.

When I know an interview could be tough, I make sure I know the interviewee has a support system for post-interview. This could be a therapist, family, or a friend — someone they confide in when they’re feeling the effects of trauma. If my budget allows, I like to set some money aside for a counseling session if needed. (More on this in a bit.)

Building a relationship

Before interview day, consider making opportunities to build rapport. Take your interviewee for coffee, or go for a walk. Help them feel comfortable in your company and learn a little bit about their body language. If it’s not possible to meet before the day itself, carve out some time before the interview to chat about normal things. Ideally, somewhere away from the cameras and equipment, like a coffee shop. If you’re in their space, accept any hospitality they offer. These small interactions can do wonders for making a person feel at ease and in control.

When building rapport, it’s important to express empathy, not sympathy. Empathy is non-judgemental and refers to the ability to understand another person’s position. Sympathy, on the other hand, can imply you pity someone, which in turn could make them feel disempowered.

Creating a safe environment

Your interview needs to take place somewhere that feels safe and comfortable. Give your interviewee a few options — it might be that they feel most comfortable at home in their own space. Equally, their home might not be appropriate.

Wherever they decide, try to make sure there’s a clear path between your interviewee and the exit. It’s not something you need to talk about, but knowing they can leave unobstructed will create a sense of psychological safety.

When speaking to your interviewee, avoid looking down at them. Place yourself at eye level or lower to avoid any power imbalance. It could also feel more natural and equitable to sit next to your interviewee, rather than opposite them. This is admittedly more difficult for filmed interviews, but it’s an option.

It’s likely your interviewee is nervous, which can muddle their thoughts and speech — we’ve all been there! By speaking softly and slowly, with relaxed body language, you’ll signal that everything is okay, and allow them the space to think more freely.

The interview

It’s important to acknowledge a person’s trauma at the start of an interview. Something like: “Before we start, I just want to say how sorry I am for what you’ve gone through. I can’t imagine what it’s been like.” According to Healey, the worst thing you can do is tell a person “I know what it’s like,” which can make a person feel as though they’re not being heard. Whatever your approach, make sure what you say comes from the heart. Your apology needs to be genuine, not transactional.

During the interview, use open-ended questions that encourage your interviewee to share their story in their own words. Allow them to guide the conversation and avoid leading or suggestive questions that may inadvertently influence their responses. Say things like “Tell me about your experience,” and “How did that make you feel?” Importantly, if they choose not to answer a specific question or to end the interview, honor their decision.

Follow-ups and self-care

Make sure your interviewee has access to support and resources following your interview. Compile a list of trusted services, helplines, or other sources of assistance in case they need help beyond their own support systems.

The day after the interview, drop your interviewee a text or call to check in on how they’re feeling. Thank them again for their time and wish them a good day.

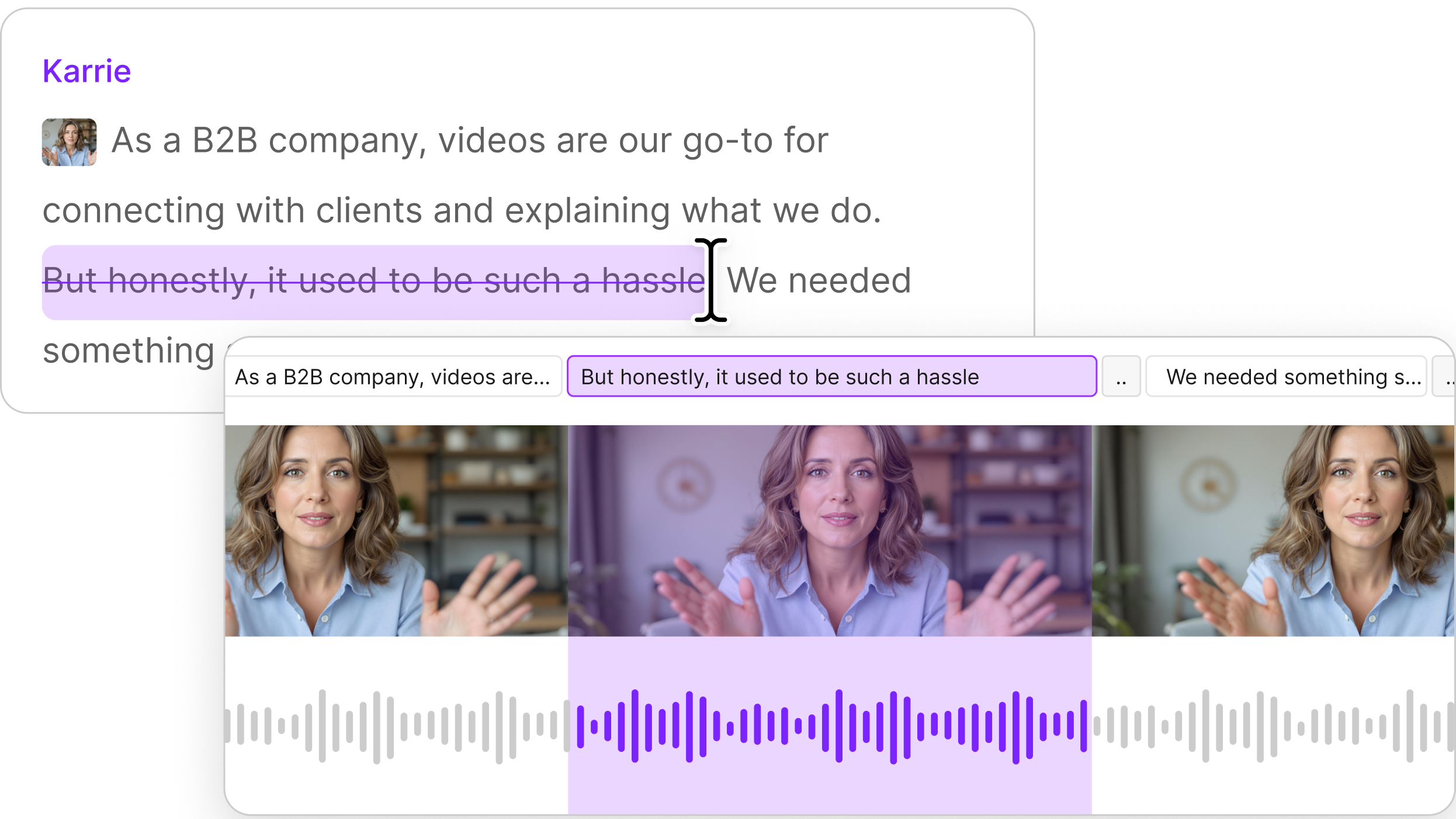

I also like to check in with my interviewees before I publish anything, to double-check that they’re happy with what I’m about to put out to the world. This can be done in the form of a transcript, or video link. It’s definitely not standard practice in journalism, and in fact, a lot of editors don’t like it, but I like to give people as many opportunities as time allows to give consent, recognizing that feelings can change over time. However, I avoid promising this protocol because often, time doesn’t allow and I don’t want to break their trust.

The most important thing is to not disappear. As a storyteller, whether you’re a filmmaker or journalist, you have a responsibility to the people whose stories you choose to tell. It takes incredible courage for people to share their stories with you and the world. Don’t take the story and run. If you can, schedule an annual courtesy check-in, or keep in touch on social media. It doesn’t need to be anything more than that.

Lastly, check in with yourself. Exposing yourself to a person’s trauma can be stressful. Being self-aware and learning to identify your own stress is an important first step for self-care. Do what you need to do to reset, whether it’s grounding meditation, your favorite outdoor exercise, or taking on some lighter projects.