Podcasting has basically become the poster child for remote-friendly work—just ask your neighbor who started three new shows last week. Whether you’re in a cramped New York apartment or on a ranch in Wyoming, you can record or contribute to a podcast with nothing more than a laptop and an internet connection.

This extends to not only the people making podcasts, but guests, consultants, and anyone you need to interview. Based in Chicago and need to bring a rancher from Montana on the pod? No problem!

As someone who has captured the audio of non-local guests via everything from tape syncs to Google Meet calls to in-studio sessions, here’s a library of options for remote audio capture ranked, in my experience, from worst to best.

Recording a phone call

|

If all you want is a quick transcription or you’re really stuck, you can record a phone call. It’ll capture the moment, but don’t expect pristine quality—phone lines compress audio into oblivion.

There are apps like Google Voice or TapeACall, but these can often be restricted by phone software, and you may need to poke around in your phone's settings to see if there’s a built-in recording option.

Either way, you won't be getting the best audio. When you talk on the phone into the device's microphone, what’s mainly getting captured are called presence frequencies. These are the frequencies of your voice typically between 4–6 KHz, and is the range of the human voice our ears are best at picking up. While that’s great for being able to hear and understand someone over the phone, it means that you miss the full spectrum of the human voice (and if your speaker has an especially high or low-pitched voice, they'll be more difficult to understand in general).

Tinny or garbled audio does not a good podcast episode make, especially if your guest is located in an area with less than stellar cell service. A phone call gets the job done, but if you can afford it production-wise, it's best to see what other methods are available.

Virtual meeting platforms for remote interviews

Virtual meeting platforms like Zoom and Google Meet are one step up from a phone call. This method works best if the guest is also recording themselves into a Digital Audio Workspace, or DAW, with a good microphone and a quiet space. I prefer to use call recordings in this situation as a backup, with the remote self-recording being the primary source. Again, if the source's connection is spotty or the video call service doesn't prioritize audio (as many rank video higher on the quality needs list), you won't be getting a great-sounding interview.

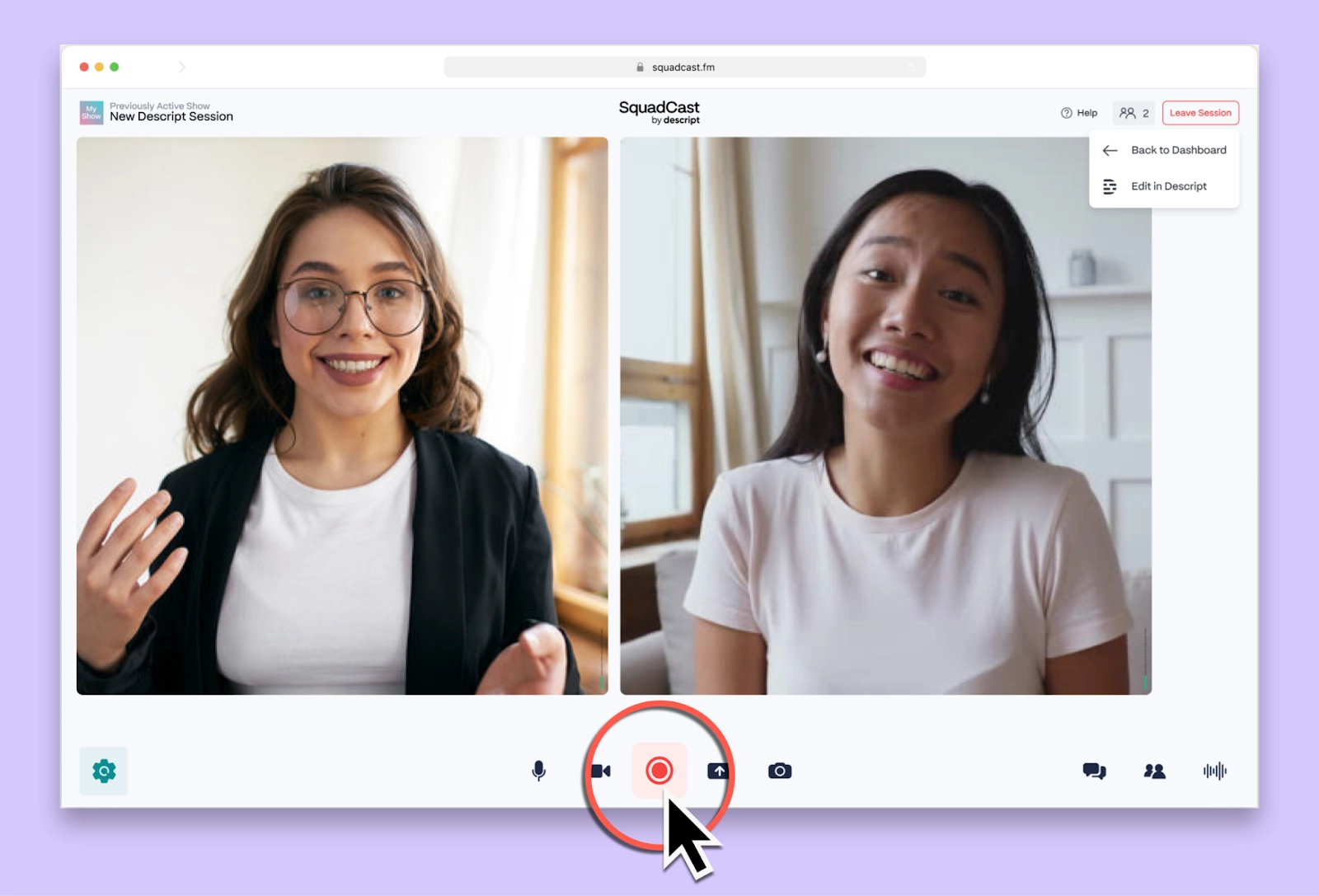

Remote recording software (such as SquadCast)

For recording video call interviews with a service that does prioritize audio quality, remote recording platforms like SquadCast are a great bet. These platforms capture recordings of each person’s audio and video at the source, negating the effect of connectivity issues on recorded audio.

|

In the case of SquadCast, it does this using a feature called Progressive Uploads. This auto-saves the call recording every few seconds as a backup for when the locally recorded call isn't available. It has integrations with Descript and other collaborative file sharing services like Dropbox for multi-person production teams, plus built-in mixing and mastering tools.

The drawback is, of course, that you can still be working with a guest who is unfamiliar with best recording practices, has a poor recording setup, or is calling in from a loud or disruptive environment. While you can't fully account for user error or extraneous environmental variables, SquadCast is still your best bet for self-directed remote recording.

Double-Ender Recording

A double-ender recording is when each person records their own audio locally, eliminating connection hiccups altogether. You’ll each end up with a high-quality track you can stitch together after the fact. Is it a bit more work? Yes, especially since your guest might need a little hand-holding if they’re not used to recording themselves. But if you want each voice sounding extra-crisp, a double-ender delivers. You can use an intuitive tool like Descript to easily sync and edit both tracks, so those little delays and janky internet artifacts never make it into the final cut.

Tape sync method

Back in college, I learned the ropes with “tape syncs”—the fancy way of getting studio-quality sound from someone who’s nowhere near a studio. Instead of subjecting your guest to a scratchy phone line, you hire a local audio tech to mic them up while they chat with you remotely. Voilà, high-quality audio from someone without a real setup.

The production will often put out a call for a tape sync needed (the Public Radio NYC email group is a great one to join for engineers looking to pick up calls, or producers looking to put them out), and an engineer local to the area will bring their recording gear to the guest's location. The engineer will set things up to capture the best quality audio possible, do the occasional bit of education on best recording practices, and either monitor the recording during the call or follow the guest and host throughout the walk-and-talk. Once the interview is finished, the engineer will send the deliverables to the production and invoice for their time.

|

What makes a great tape sync is twofold: gear and professionalism. Productions will often ask for a list of the engineer's gear when choosing who to hire because they want to ensure that said gear is not only of good quality, but right for the job at hand. I have both a stationary kit containing a mic stand, a pop filter, a small portable preamp, and my AT2020 (which has a flat frequency response, making it a great-sounding mic for a range of voices), as well as a more portable kit with a Zoom H4n recorder and a windscreen.

Professionalism is also key: keep things polite, don't be afraid to ask questions about the space or the production's needs, and be punctual. Many shows with the resources to do tape syncs come from larger production houses with tight schedules who value quality and need their audio recorded and sent promptly.

The variety of options for gathering remote audio can sometimes feel overwhelming with some more obviously preferable than others, but it’s important to remember that each can be the best fit for certain situations. Sometimes your guest can only be reached over the phone; sometimes their connection is spotty and you need a constant backup of the recording; sometimes there’s a line item in the budget for a tape sync and sometimes there isn’t. The strongest tool in your toolbox is to know what your options are, and when each one is the best fit.

Frequently asked questions

How do I record a remote interview in Descript Rooms?

In Descript, click New project and choose Descript Rooms. Invite your guest using the session link. Once you both join, Descript creates separate high-quality tracks for each speaker—no separate apps required. After recording, you can edit the audio and video in Descript.

Can I record a remote interview in Descript using Zoom or Google Meet?

Yes. You can record a Zoom or Google Meet call, then drag the file into Descript for editing. If you prefer real-time local recordings, use Descript Rooms for higher-quality tracks without extra steps.

Do I need special gear to record remote interviews in Descript?

Not necessarily. A stable internet connection, headphones, and a decent mic help a lot—such as a USB microphone and wired earbuds. Descript’s Studio Sound feature can also enhance audio quality, even if guests use basic gear.

Does each speaker get their own track after recording in Descript?

Yes. Descript automatically creates separate audio and video tracks for each participant. This makes post-production more flexible, so you can edit individual voices or remove distractions on one track without affecting others.