This article originally appeared in Episodes, our newsletter. If you'd like insights on workflow and craft (like these) in your inbox every two weeks, you can subscribe here. Or listen to the audio version (read, without irony, by Ashley's Overdub Voice.)

If you speak into a mic, eventually you’re going to have to read into a mic.

Even if you’re making a seat-of-the-pants roundtable show, you probably have scripted intros for episodes and guests, an outro to plug your social media platforms, maybe a few host-read ads. And if your show is scripted — a narrative nonfiction podcast, a science-explainer video series, or an audio showcase for your unpublished avant garde fiction, for instance — you live and die by reading out loud.

It should be easy. But when we read into a microphone it somehow comes out sounding very different than when we’re just talking. At worst we sound stilted, or robotic. At best our delivery is too clean, lacking the natural inflections and flaws that mark our personalities.

So how do you make those perfectly arranged words on the page sound like the messy, chaotic, lived-in speech that we all use to talk to each other? Plenty of creators have mastered the craft; we talked to a few, and here’s what they had to say.

Write it out

Reading in a way that sounds natural starts with writing for listeners, not readers. That might mean forgetting a lot of what you’ve learned about writing.

Most of us have been taught to write formally, in structured paragraphs and long, information-packed sentences. “When you start writing for voice, you need to ditch all of that,” says writer and podcaster Sanden Totten.

He should know. As a former science reporter for Southern California Public Radio, a writer for Netflix’s Bill Nye Saves the World, and co-creator of the award-winning kid’s science podcast Brains On!, Sanden has spent his career writing scripts to sound like they’re improvised.

The audio writing rules he learned early in his career are helpful for anyone learning to write for their own speaking voice.

- Short, simple sentences. If there are two ideas in a sentence, turn it into two sentences. You’ll give yourself time to breathe when you read it aloud, and it’ll sound closer to the way most of us talk. It’s also easier on the listener, who’ll be less likely to get lost in the thickets of your run-ons.

- Simple vocabulary. You want to sound smart, and you might be tempted to use words you memorized for the SAT, but the goal here is clarity. Multisyllabic words, such as multisyllabic, catch a listener’s attention alright, but they’ll focus more on the word than on the point you’re trying to make.

- Break the rules. In fact, ignore them. “It’s important to get your grammar correct, but it’s not that important,” Sanden says. Use the turns of phrase you use in natural speech. You’d never start an essay sentence with “So,” or “I mean,” or “What I’m thinking is,” but you probably do that all the time in conversation. (Yes, Descript calls these Filler Words. But filler is like gas station pastries – sometimes you just need it.)

Once you’ve written your script, record yourself reading it, play it back, and listen closely. If there are words or phrases that sound stilted or robotic, rewrite and re-record until everything sounds natural.

Read, read, read again

Sounding natural takes practice – a lot of it. Brian Noonan is radio host at WTMJ Milwaukee and a former host at WGN Radio in Chicago. Even though he’s been talking into a mic full time for nearly 15 years, he still has moments when his reading feels unnatural. Nine times out of 10, it’s because he didn’t get a chance to read the copy beforehand.

Brian advises reading your script out loud over and over until you’re comfortable with it. And then, a real pro tip: As you read, ask yourself what each word is trying to say — what tone it’s trying to take, and what feeling it’s trying to elicit. The biggest difference between talking and reading is emotion, so pinpoint the emotion you’re trying to convey.

Once you have that, you can fine-tune your delivery. Adjust your speed and volume. Decide where you need to add emphasis. Note the words that are tripping you up, and either change them or keep repeating them until you can get through them smoothly.

Then, add cues to your script. “If I know I’m supposed to go up here or I’m supposed to go down here or [take] a longer pause, I’ll get my highlighter or my pen and I’ll mark it up,” Brian says.

Get physical

There’s one more difference between talking with your friends in a bar and reading words behind a microphone: what you do with your body. No one can see your hand gestures through their headphones, but they can certainly hear it in your voice.

To prove it, Sanden suggests trying one readthrough with your hands by your sides and another gesticulating wildly. You’ll probably sound a lot more animated and energetic the second time around. “It’s almost like you’re orchestrating yourself,” he says.

If your gear permits it, try standing up. It’s almost impossible to sit hunched over a microphone in an empty room and bring the same energy as you would from your feet. Standing not only gives your lungs more space to expand, but it also gives you focus. “If I’m standing up, I’m in the moment,” Brian says.

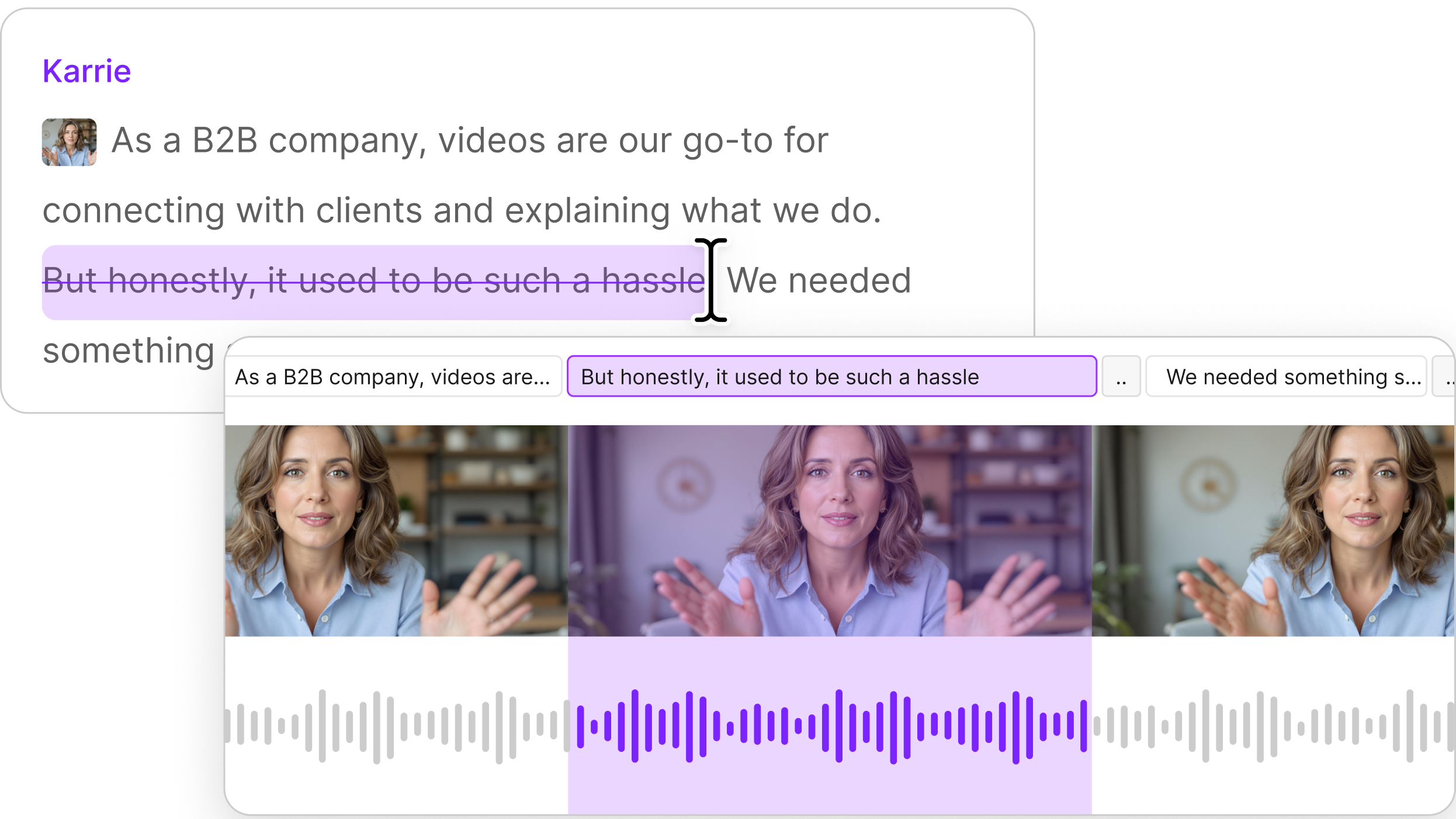

One final piece of advice for recording. As you read in your script, try to stay attuned to how much Reading You sounds like Real You. If you hear yourself speaking a sentence that doesn’t feel natural, just pause and say it again, the way you would to that mythical friend in the bar. If you’re working in Descript, you’ll be able to edit the first version out in a few seconds.

There are plenty of minor details to obsess over once you get the basics of reading down (What tone of voice should you take? Should you refer to the audience in the singular or the plural? Is it de-SCRIPT or DEE-script?) but there’s no need to overdo it. Just focus on writing like you talk, reading it over a few times, and moving your hands while you speak, and the rest will come with time.